Or … Did J.D. Vance Kill Pope Francis?

In January, 2025, new Vice-President J.D. Vance, speaking with Sean Hannity, asserted that the recently announced Trump administration elimination of the Agency for International Development, or foreign aid in general, was based upon a Christian (Catholic) doctrine dating back to Augustine, called Ordo Amoris. Vance was gaslighting Hannity and his followers. He was flaunting his recent conversion to Catholicism by referring to a concept which most had never heard – and which Pope Francis immediately felt compelled to refute in a letter to U.S. Bishops. Vance and Francis met briefly on Easter Sunday, April 20. Francis was dead the next day. We don’t have any clear record of what transpired in that final meeting.

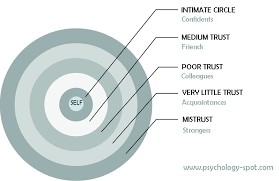

But one thing is clear to me, a secular writer on ethics, politics, and philosophy: Francis was right, Vance was wrong. It seems the Vice-President, in January, was conflating the Augustinian conception of Christian love (elaborated by Aquinas in his Summa Theologica) – that it must start with God and only then be applied to others, incidentally arranged in groups according to some natural order — with the modern psychological model of “circles of trust.” We tend to trust the outer circles of our world less than the inner circles of our family and community. Francis’ rebuke of Vance focused on the parable of the Good Samaritan. Love must extend to all humanity – and it is aspirational, not descriptive.

The idea of Circles of Trust – unlike Augustine’s original Ordo Amoris – has a theological connection only so far as we live in a world of finite resources (including time), forcing us to prioritize our good works. Not only Pope Francis, but even Martin Luther, had serious issues with “self-love” being the center of the universe. Today, I’m more concerned with the implications of those concentric circles of trust and the twisting of that concept into artificial antagonisms that exploit lack of trust in others — like “owning the libs” and all those “anti-woke” ministrations. Is there anything to be gained from civil war in our society? Try as he might, J.D. Vance cannot convince me that justice will be served by encouraging further divisions among different ethnic and cultural groups — within our country any more than between our country and the rest of the world. Wars are bad, whether civil or international.

While the simplest psychological diagram of circles of trust starts with “self” in the center, then radiates out through five concentric circles labeled “intimate circle,” “medium trust,” “poor trust,” “very little trust,” and “mistrust” – pick whatever labels you choose for each circle. The point is that the greater your interaction, and mutual dependence, with a certain group, the greater your trust in that group. What is noteworthy about this scheme is that closer means greater trust, distance means less trust. But what about things like advancing telecommunications – our ubiquitous smart phones? Shouldn’t they cause increasing trust among all groups, by closing the “distance” between them? Aren’t we all “closer together” than in former times? Apparently not. Those smart phones all contain different apps – and the apps built on different algorithms – with the result being we now trust others less than we used to! The General Social Survey finds that over two generations, the level of trust Americans have in others (defined by agreement with statement: “Most people can be trusted”) has declined by some 12 points.

If we assign social/cultural labels to those five circles of trust: “family,” “friends,” “community,” “cultural group (nation?),” “humanity” – we see a troubling tendency toward greater atomization of society. Exploiting that declining level of trust also seems to be the political goal of certain unscrupulous actors: Divide and conquer! J.D. Vance and the Trump administration fit squarely into that mold. They apparently feel their success somehow depends on exacerbating the increasing tensions of American society — shrink the diameter of the inner circles and broaden the outer circles. Right-wing populists in other countries have adopted the same playbook. Meanwhile, the Left (such as it is) is relegated to repetition of ancient Christian (and Jewish and Muslim) admonitions to love all mankind, especially “the least” of them – perhaps even including nature itself (climate activism). I’m not sure where all this leads – but I’m apprehensive. Is some sort of mass mobilization necessary? A few of us Marxist/anarchist holdovers muse about “vanguards” and “movements,” but won’t that facilitate the awful civil war we fear?

In 1992, Rodney King, who had been beaten and arrested by L.A. police the previous year, made a statement after the acquittal of the officers who had beaten him, and the subsequent riots against police brutality in the city. His statement became famous, paraphrased after being aired on TV: “Can’t we all just get along?” This was an exasperated expression of what many Americans, both Black and White, would feel repeatedly over the next few decades – after 2014 Ferguson, MO, and again in 2020 during Black Lives Matter protests. There is, unquestionably, deep underlying conflict in America – whether based on race, gender, or class … or all three. But even if it is all lumped together as “woke” vs. “anti-woke,” it is not pleasant. Those of us who value peace – and equate it with justice – view with disgust the political tendencies to exacerbate the conflicts rather than resolve them. Winning should consist of conflict resolution, not suppression of dissent. We need to keep in mind the basic premise of social conflict: some groups want to get more (perhaps what they “deserve”) and other groups merely want to preserve what they have (hence, are threatened by the first group who want to take it!). In a world of scarce resources, such conflicts will likely persist. There are only two ways to resolve these conflicts: 1) alleviate the scarcity (so that all may get more), and 2) accept the inequality as just (historically, a losing proposition). As we progress through our civilization’s story, we tend to see these conflicts as innate – never to be resolved – and our task is merely to choose a side. Taking the first path toward conflict resolution leads mostly to technocracy, taking the second path leads to autocracy. I favor technocracy myself.